By Dan Reich

Photos by Ellen Goldstein

On the outskirts of Amboseli National Park in Kenya, we visited a small Maasai Village to learn about the lives and customs of its inhabitants. But after discovering that we were Americans, everyone in the village wanted to know: were we going to vote for Obama?

Their keen interest in the U.S. election was an indication of a culture in transition. For hundreds of years, the Maasai have been semi-nomadic tribes, relying on livestock and shelters built from sticks and mud. Relatively isolated from the influence of the western world, they’re fiercely proud  of their traditional lifestyle, but also aware of the benefits that tourist dollars can bring, from freshwater wells to schools and bathrooms.

of their traditional lifestyle, but also aware of the benefits that tourist dollars can bring, from freshwater wells to schools and bathrooms.

With global warming, as evidenced by the disappearing snow on Kilimanjaro, access to water is more vital than ever, and Maasai children are educated to prepare for the modern world. This education allows them to gain employment outside the village, providing funds to help improve their lives while preserving their traditions. Tourism has thus become an essential part of Maasai life, and they go to great lengths to share their way of life and make you—their guest—feel welcome.

Our safari guide, Divan, arranged for our visit, which cost $30 per person. We were allowed to take as many photos as we wanted. Upon arrival, a row of women in bright sarongs and festive ornamental beadwork sang a traditional welcoming song with sweet call-and-response harmonies.

of their traditional lifestyle, but also aware of the benefits that tourist dollars can bring, from freshwater wells to schools and bathrooms.

of their traditional lifestyle, but also aware of the benefits that tourist dollars can bring, from freshwater wells to schools and bathrooms. With global warming, as evidenced by the disappearing snow on Kilimanjaro, access to water is more vital than ever, and Maasai children are educated to prepare for the modern world. This education allows them to gain employment outside the village, providing funds to help improve their lives while preserving their traditions. Tourism has thus become an essential part of Maasai life, and they go to great lengths to share their way of life and make you—their guest—feel welcome.

Our safari guide, Divan, arranged for our visit, which cost $30 per person. We were allowed to take as many photos as we wanted. Upon arrival, a row of women in bright sarongs and festive ornamental beadwork sang a traditional welcoming song with sweet call-and-response harmonies.

The men engaged in the adumu, or “jumping dance.” They invited me to jump with them, chuckling at my relatively modest heights. Then we were introduced to our host, Wilson… a tall, articulate man who would soon replace his 92-year-old father as Chief. He escorted us through a gap in the circular fence of thorn acacia that protects the village and its livestock from predators.

Several dozen mud huts were arranged on the perimeter of the village, while the dusty center was reserved for the livestock at night. Small groups of men played mancala as a medicine man’s apprentice explained the roles of various herbs, including one to boost virility and another to suppress the growth of a fetus late in pregnancy to reduce the likelihood of complications in childbirth. Another villager lit a small fire by rubbing sticks together.

apprentice explained the roles of various herbs, including one to boost virility and another to suppress the growth of a fetus late in pregnancy to reduce the likelihood of complications in childbirth. Another villager lit a small fire by rubbing sticks together.

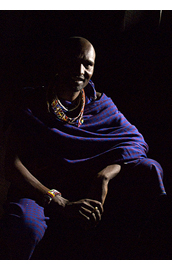

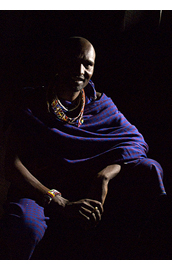

We were honored when Wilson invited us into his living quarters. Stooping to enter through a small door, we found ourselves in near darkness. A tiny opening provided dim light as our eyes struggled to adjust. In the single room, a few stones on the floor formed a cooking area, and several platforms of cowhide stretched over a framework of sticks served as beds. Wilson, his regal form silhouetted against the darkness, described the traditional Maasai diet of meat, milk and blood and the polygamous family structure. (The wives don’t mind, he said, as they share household duties.) Emerging from his hut, I couldn’t help but notice padlocks on other huts… a sign that modern life was making inroads against the traditional lifestyle around us.

household duties.) Emerging from his hut, I couldn’t help but notice padlocks on other huts… a sign that modern life was making inroads against the traditional lifestyle around us.

A marketplace was spread out on blankets behind the village, with dozens of women offering wedding necklaces, bracelets and beaded baskets, The earnest friendliness of the villagers made it hard to refrain. Wilson tried to make sure we bought something from each of his many wives. Eventually, we wound up with a sizable collection of souvenirs. Wilson proudly pointed out a new schoolhouse a few hundred yards away and described the new well that saved a six-mile trip to the watering hole. Our contribution to the Maasai economy was being well spent.

As Wilson bade us farewell, he reminded us to “vote for Obama, the son of a Kenyan.”

Several dozen mud huts were arranged on the perimeter of the village, while the dusty center was reserved for the livestock at night. Small groups of men played mancala as a medicine man’s

apprentice explained the roles of various herbs, including one to boost virility and another to suppress the growth of a fetus late in pregnancy to reduce the likelihood of complications in childbirth. Another villager lit a small fire by rubbing sticks together.

apprentice explained the roles of various herbs, including one to boost virility and another to suppress the growth of a fetus late in pregnancy to reduce the likelihood of complications in childbirth. Another villager lit a small fire by rubbing sticks together. We were honored when Wilson invited us into his living quarters. Stooping to enter through a small door, we found ourselves in near darkness. A tiny opening provided dim light as our eyes struggled to adjust. In the single room, a few stones on the floor formed a cooking area, and several platforms of cowhide stretched over a framework of sticks served as beds. Wilson, his regal form silhouetted against the darkness, described the traditional Maasai diet of meat, milk and blood and the polygamous family structure. (The wives don’t mind, he said, as they share

household duties.) Emerging from his hut, I couldn’t help but notice padlocks on other huts… a sign that modern life was making inroads against the traditional lifestyle around us.

household duties.) Emerging from his hut, I couldn’t help but notice padlocks on other huts… a sign that modern life was making inroads against the traditional lifestyle around us.A marketplace was spread out on blankets behind the village, with dozens of women offering wedding necklaces, bracelets and beaded baskets, The earnest friendliness of the villagers made it hard to refrain. Wilson tried to make sure we bought something from each of his many wives. Eventually, we wound up with a sizable collection of souvenirs. Wilson proudly pointed out a new schoolhouse a few hundred yards away and described the new well that saved a six-mile trip to the watering hole. Our contribution to the Maasai economy was being well spent.

As Wilson bade us farewell, he reminded us to “vote for Obama, the son of a Kenyan.”

If you wish to purchase this article for your publication, click here to contact the author directly.

All Photos © 2008 Ellen Goldstein