And in the middle is you, perched on one of Lawrence of Arabia’s legendary “ships of the desert.” It’s letting out the most embarrassing moaning and groaning sounds, bleating and bellowing and roaring in indignation. You try to emulate a Saudi princess bedecked in flowing robes and unfathomable Khol-rimmed eyes.

Then you’re flung violently forward as the creature lurches upright, back legs first, complaining loudly the whole time.

Then you’re flung violently forward as the creature lurches upright, back legs first, complaining loudly the whole time.

You start off. The slow, deliberate lope of a camel is surprisingly calming. Confidence resounds through the beast as strongly as the breath of its mate behind you.

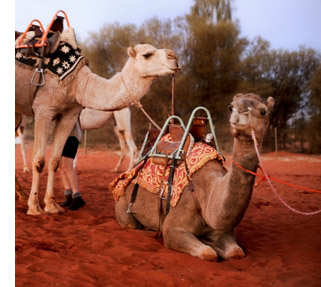

The camels used by Uluru Camel Tours are dromedaries, the one-humped variety native to Asia and well suited to the semi-arid climes of the Australian Red Centre.

Brought here along with Afghan handlers by European settlers, their job of carrying bulk supplies to Outback towns like Alice Springs, mining communities and pastoral stations was eventually superseded by trucks and trains and they were released into the wild.

At their peak, there were about 20,000 working camels in Australia. Today, there are about a million wild ones roaming the desert plains, free to stare down cars and campervans from the middle of the 130km/h highways.

Efforts are being made to establish a camel industry (to process camel by-products) and a live camel export trade.

Businesses like Uluru Camel Tours catch wild camels aged between four and six for use on tourist trails. Typically having the intelligence of a six-year-old child, they are fairly easy to train, Rohin says.

Businesses like Uluru Camel Tours catch wild camels aged between four and six for use on tourist trails. Typically having the intelligence of a six-year-old child, they are fairly easy to train, Rohin says.

“Working with these guys can certainly be challenging. Trying to wake them up at 5:30 in the morning can be quite interesting. But they are certainly amazing creatures. They’re our mates.”

Rohin leads the caravan on foot carrying a long stick. There’s no clear reason for it—the camels know the routine, and apart from Alice, who keeps threatening to sit down, they are all well behaved.

Every now and again Rohin stops to give a snippet of information about the environment, the history or indigenous Anangu culture.

My journey ended just as crotchety old Tamani and I were beginning to fall into a rhythm. He’d fallen silent and I, with the warmth of his wool against my legs, had let my thoughts drift with the sands of the “never-never” to pleasant places tinted with the desert sunset.

The growling started up again and we were reminded to stay in our saddles until a handler approached. Camels have a habit of lurching to their feet as soon as they settle on their haunches, leaving distressed tourists hanging by one foot from the stirrups.

A parting piece of trivia: camels don’t spit. That’s left to their cousins the alpacas. No, camels throw up. According to San Diego Zoo, this unpleasant trait is to “surprise, distract or bother whatever the camel feels is threatening it.”

How to get there:

How to get there:The camel farm is within the Voyages Ayers Rock Resort complex. Regular Qantas flights leave from most Australian cities. The area can also be accessed by the sealed Lassetter Highway.

How much:

$99 for 2.5 hour sunrise and sunset tours includes transfers from accommodation

$65 for 1.5 hour Camel Express

$10 adult, $5 children (5-15) for ride around the camel farm yards

$25 per person 16 years and over for Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park entry

Details and bookings:

Anangu Tours: +61 08 8950 3032 or reservations@anangutours.com.au

When to go:

The safest and most comfortable time to visit the Australian desert is during the cooler months of April to October.

Where to stay:

Voyages Ayers Rock Resort is the only accommodation near Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. However, it offers a range of packages from campsites to five-star and prestige rooms. Details and bookings: http://ayersrockresort.com.au, 1300 134 044 or travel@voyages.com.au.

The author and photographer enjoyed a complimentary camel ride with Uluru Camel Tours thanks to Tourism Northern Territory.

If you wish to purchase this article for your publication, click here to contact the author directly.