Four hundred years ago it would have been the smell of grilled heretics rather than croissants wafting to my nostrils in Toledo’s Zocodover Plaza. The spirit of the Inquisition has never completely left.

Four hundred years ago it would have been the smell of grilled heretics rather than croissants wafting to my nostrils in Toledo’s Zocodover Plaza. The spirit of the Inquisition has never completely left.

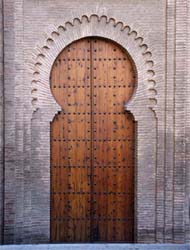

Entering through the great Nueva de Bisagra gate, whose double-headed eagle looks like a prop from an old Hammer film, you’re immediately thrown into a maze of narrow streets. The medieval  buildings have that unique blend of heavy gothic softened with Arabic elegance from Moorish times that is found across Spain.

buildings have that unique blend of heavy gothic softened with Arabic elegance from Moorish times that is found across Spain.

All streets lead to the cathedral. The poet Garcilaso de la Vega described Toledo as “a clear and illustrious nightmare,” and this building is at the heart of the uneasy dream, a distillation of many disturbed nights. Its darkly glittering interior made me think of Francis Bacon’s screaming Popes. It is all gold and jewels, ancient ironwork, enraptured faces in stone and paintings of saints flickering in the candlelight.

The crowded main street, the Calle del Angel, with its trinket shops and tapas bars, leads you to the Monasterio de San Juan de Los Reyes on the western edge of the city.

Here there is a spectacular view across a parched landscape, and a welcome cool breeze. The walls of the 15th century Franciscan monastery are decorated (if that’s the right word) with the fetters of Christian prisoners of the Moors. Most modern cities have such relics hidden away in museums or vaults, sanitising their past into guidebook versions of history.

But I think Toledo would agree with William Faulkner: “The past is never dead, it’s not even past.” Once a stalwart defender of the faith, Toledo in its old age refuses to let go of the old ghosts. Stakes and leg irons define the city more than trinket shops.

Most important information about generics